Sometime between the spring and fall of 1848, Levi Strauss, his mother Rebekka and his two sisters Mary and Fanny left their home village of Buttenheim, in Bavaria. Levi’s two oldest brothers had emigrated to New York a few years earlier, and were sending back glowing reports of their success and prosperity in the dry goods business. There were no economic opportunities for a young man in Buttenheim, especially since Levi’s father had died in 1846. So, the remaining family members decided to take their own chances in America. Once packed, and their goodbyes said, they headed to Bremen to catch the next New York bound ship.

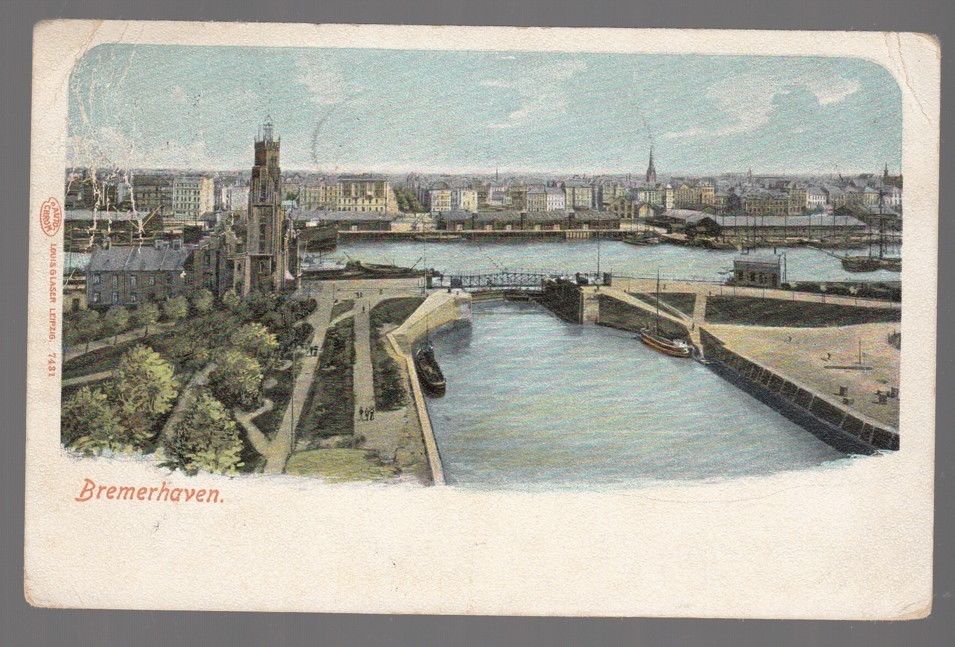

Once in Bremen, voyagers had to wait for a few days to get seats on a steamboat to take them up the Weser River to Bremerhaven, which was the actual port city. This took about five hours, depending on the weather. As Bremerhaven came into view, people like the Strausses, accustomed to village life, could only have been astounded at what they saw.

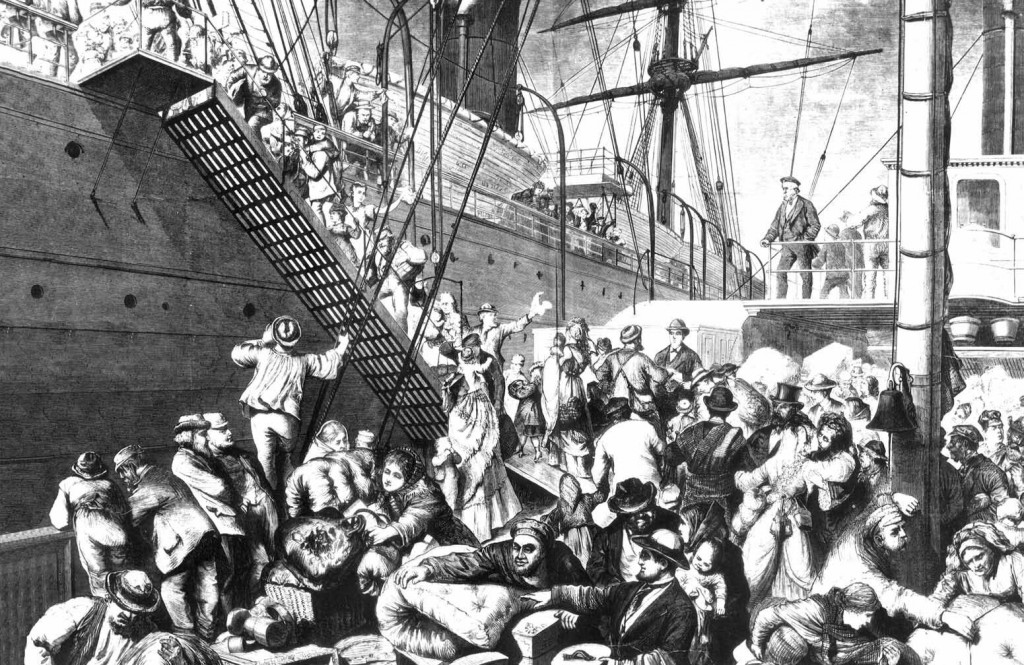

Passenger and merchant ships bobbed and bumped against each other at the dock, sails flapping. Sailors and dockhands loaded and unloaded both goods and people, accompanied by the sounds of creaking ropes, tumbling boxes, wheels on stone, and no doubt, startling profanity. The smells were probably equally surprising.

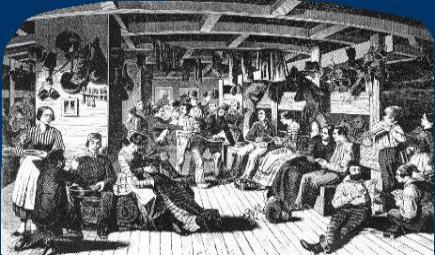

The ships which took emigrants to the States were often freighters as well, carrying American goods like cotton and tobacco to Europe, and returning to the U.S. filled with passengers. The Strauss family probably traveled in steerage, and not in one of the above-deck cabins, which were much more expensive. It was called the “between decks” because it was located below the main deck and above the hold where freight was stored. And even the best designed, most spacious steerage accommodations were a rolling, tumbling, dark, watery, waste-filled hell that emigrants remembered for the rest of their lives.

Each passenger had about fourteen square feet of space to live in, and which might only be about six feet at ceiling height. This they shared with a bolted-down type of bunk bed, along with provision boxes, designed to keep rats and other vermin from either the food or precious personal items stored inside. These were sold by the hundreds in departure cities like Bremen. If passengers were able, they also squeezed in things like cutlery, and perhaps a chamber pot. Nails were driven into the wall for hanging clothing, meats, cheeses and other preserved foods. Everything beyond what they had on their backs took up precious space, making the journey, which could last from four to twelve weeks, even more claustrophobic. And if there weren’t enough people to fill the steerage area the empty spaces were often stuffed with cargo.

When seas were calm, steerage passengers could sit on their beds, mingle with each other, and even go up on deck. But during storms or periods of great winds, they had to stay below and just hold on; to themselves, their families and their belongings. Anything not stowed or otherwise secured could slide dangerously along the floor. And not even the largest chamber pot could hold the volume of vomit that accompanied the seasickness of the first few weeks on the water.

Some emigrants recorded their shipboard experiences in diaries. Abraham Kohn left Bavaria in 1842 and also voyaged to New York out of Bremerhaven. He endured a long sailing of about seventy-two days thanks to a storm which shattered one of the ship’s masts, more wild weather, and disappearing winds.

“Life on board ship is extremely tedious,” he wrote on July 30, 1842, eighteen days after leaving port. “The indifferent food and uncomfortable beds are depressing, and only hope and the constant companionship of our fellow men keep up our spirits.” Sightings of whales and icebergs alleviated some of the tedium, but when there was no wind, “…the boredom is hardly to be tolerated.”

Reminders of mortality included shipboard deaths and, on Kohn’s voyage, watching the remains of a shipwreck floating past their vessel. “How many, O Lord, have found their lonely grave in the waves?” Kohn wrote. “And yet, seen from land or considered in some inland port, the idea of a wrecked ship seems to arouse even more horror than does the actual sight at sea . . .” In the next paragraph, Kohn changes direction and describes a glorious sunset, which was “. . . an inspiring sight for all of us!”

No doubt Rebekka, Levi, Mary and Fanny experienced just how ghastly a passage in steerage could be. If they were lucky, they also had moments of wonder and awe, as well as favorable breezes. Then, finally, they staggered up on deck to wait for their first view of the city of New York.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lynn Downey was the Levi Strauss & Co. Historian from 1989 to 2014. She is the author and/or co-author of nine books on the history of the West, including a number of works about the history of LS&Co. She has also published over thirty articles and book reviews. Lynn is currently at work on a biography of Levi Strauss, which will be released in 2016. Her website is at http://www.lynndowney.com.

Lynn Downey was the Levi Strauss & Co. Historian from 1989 to 2014. She is the author and/or co-author of nine books on the history of the West, including a number of works about the history of LS&Co. She has also published over thirty articles and book reviews. Lynn is currently at work on a biography of Levi Strauss, which will be released in 2016. Her website is at http://www.lynndowney.com.