Levi Strauss arrived in San Francisco in 1853, and expected to stay in the city permanently. In doing so, Levi knew he would occasionally be called upon to perform everyone’s civic duty: serve on a jury.

He had all the required qualifications. He was over twenty-one, had become a citizen, and by the time he was first called up for jury duty, he had lived in California for over six months. Prospective juror names were chosen from voter poll lists, which had been required in California since 1850, which means he was also a regular voter.

He caught a prominent case for his first time in the jury box. Thomas N. Cazneau, Brigadier General of the California militia, had a longstanding feud of some kind with Zebedee M. Quimby, a watch maker and jeweler. The two men “ …had for some time been mutually disgusted with each other, and had previously had difficulties.” On the night of November 21, 1858, they happened to meet in Blum’s clothing store on Montgomery where, after they exchanged a few heated words, Cazneau raised his cane and struck Quimby three times on the head and face. Quimby tried to fight back, but didn’t have a weapon. Cazneau was arrested, indicted and put on trial on February 22, 1859.

Since the Cazneau was a prominent local character, the case was closely followed by the city’s residents. And in the end, the jury took only one day to decide his fate. On the 23rd, the jurors found him guilty, and he was sentenced to pay twelve hundred dollars or spend three hundred fifty days in jail. Since he was working as an insurance adjuster by the following year, it appears Cazneau paid his fine. In reporting the outcome, the Daily Alta California newspaper echoed the sentiments of the jurors by describing the case as one in which “…the public peace was violated and the law insulted.”

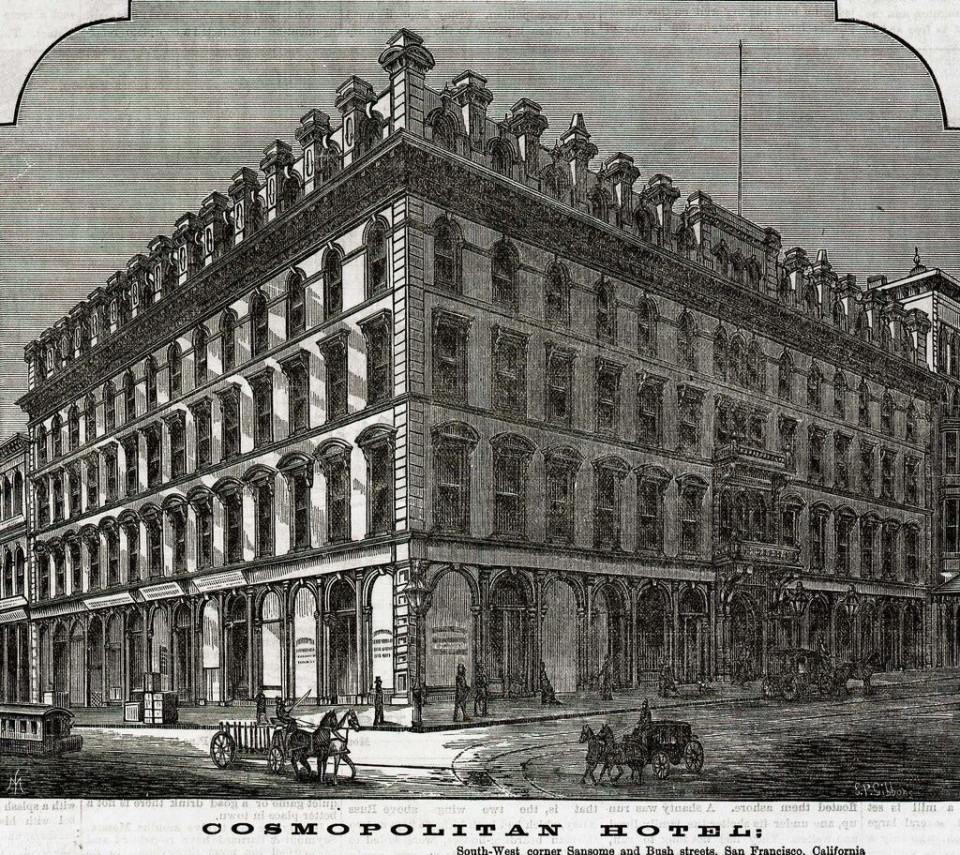

Nine years later, Levi served on a jury in a case that put Cazneau in the shade: the trial of Andrew Jackson Stevenson, accused of raping Martha MacDonald at the Cosmopolitan Hotel in February of 1866. She was in the city and staying at the hotel without a chaperone. Stevenson was put on trial in January of 1868, and the case rivals any “he said/she said” case of our own time. Allegations of immoral character, bastardy (MacDonald had a child after the alleged rape) and insanity on MacDonald’s part, were contrasted with the apparently upstanding citizenship and activities of Stevenson. He was a wealthy businessman who owned a substantial property downtown called the Stevenson’s Building, and who claimed that Macdonald entrapped him. The case was heard for ten days in the courtroom, and after thirteen hours of deliberation, the jury found him not guilty.

The verdict, coming on the heels of testimony which had been “…very generally read and commented on by the public at large” was not a surprise. And it indicates something going on under the surface of San Francisco’s wide-open, free-wheeling personality: the city would not tolerate women stepping outside of the rules that society set for them without punishment. Did Levi also believe this? We’ll never know. Merchants counted on order within society to keep business flowing, and without a solid demonstration of a woman’s good character, witnesses or other irrefutable evidence, no jury would convict a man who made substantial contributions to the city’s prosperity.

Between 1864 and 1902 Levi also served occasionally on the Grand Jury. In the years after the Civil War he became more well-known, a man of substance and influence. This would not only serve him well as his business grew, but also give him a platform to help shape San Francisco’s future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lynn Downey was the Levi Strauss & Co. Historian from 1989 to 2014. She is the author and/or co-author of nine books on the history of the West, including a number of works about the history of LS&Co. She has also published over thirty articles and book reviews. Lynn is currently at work on a biography of Levi Strauss, which will be released in 2016. Her website is at http://www.lynndowney.com.

Lynn Downey was the Levi Strauss & Co. Historian from 1989 to 2014. She is the author and/or co-author of nine books on the history of the West, including a number of works about the history of LS&Co. She has also published over thirty articles and book reviews. Lynn is currently at work on a biography of Levi Strauss, which will be released in 2016. Her website is at http://www.lynndowney.com.